Values-based leadership: show them what you are made of

If you are a business leader, you face daily decisions that you probably never thought you would face. Whether these decisions have been forced upon you by circumstance or you’ve been surprised by an unforeseen challenge or unexpected opportunity, leaders feel the business landscape shift beneath their feet today more quickly than ever. Rapid change and upheaval naturally give leaders cause to question themselves, their decision making, and to wonder whether the skills that have brought them success will continue to work in the new reality that is emerging around them. Some leaders dismiss such introspection as self-doubt and quickly move on. However, the best leaders lean into these moments and embrace them.

Every leader is responsible for the lives and livelihoods of those who depend on them. They have a duty to ensure that their leadership is worth following. So how can leaders ensure a steady hand as they navigate their firm through uncharted waters? Look to your values.

Values-Based Leadership

I encourage you to read Carl Anderson’s 1997 article, Values-based management, published by the Academy of Management Perspectives. While some aspects of his work have not aged well, such as the reliance on eastern collectivism and western individualist tropes, the Values-based leadership model he presents is still a useful framework for leaders seeking insight to improve performance in turbulent times. Here’s a high-level overview:

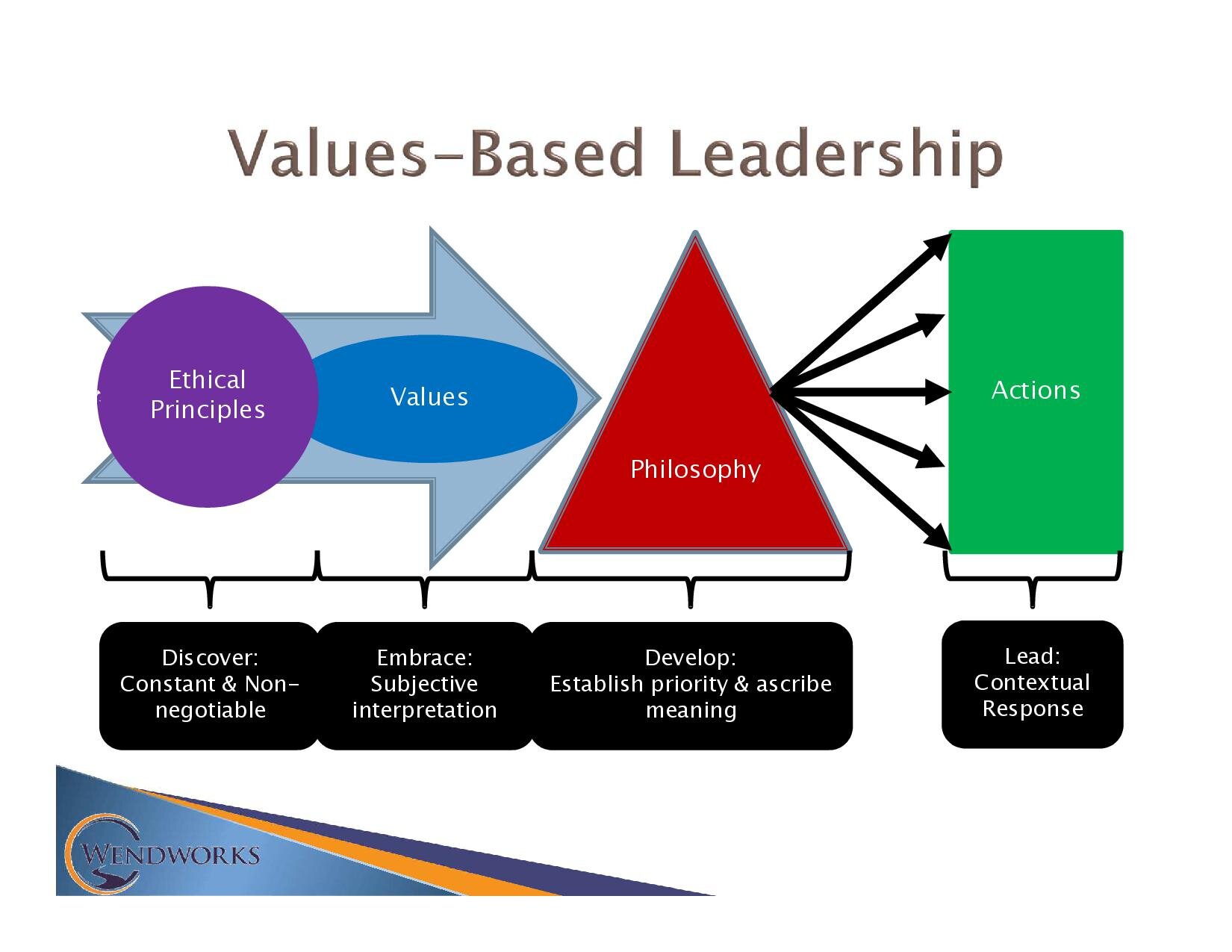

For Anderson, Values-based leadership begins with ethical principles. These principles are defined as a type of cultural constant that remains unchanged and “non-negotiable” across people and cultures. Whether these principles derive from social norms, faith traditions, or lived experience, they are the collective definitions for “what is commonly meant by a good society” (p.26) and are discovered and received by leaders rather than invented. “[P]rinciples cannot be abandoned because of competing analyses; they are prescriptive, universal, overriding, provide truths on which to base attitudes and actions, and provide a compelling reason for doing one thing rather than another” (Anderson p. 26-27). In his model, the foundational task for Values-based leaders is to discover and adopt the ethical principles that will become the values that guide their leadership.

While there are an infinite number of possible value-statements, Anderson contends that values generally fall into one of six archetypes:

General beneficence: epitomized by the Golden Rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do until you (Matthew 7:12).

Justice, honesty, and fairness: embraces “honest losses” over “shameful gains," avoids shortcuts, and refuses to embellish or under-deliver on promises while prioritizing transparency between stakeholders.

Mercy or compassion: centers on the believe that everyone, including the weak, have worth and that those with means have a responsibility to care for others.

Frugality or economic efficiency: focuses on eliminating waste in all its forms including capital, labor, materials, and processes. Often accompanied by a sense of stewardship as anything deemed unnecessary is stripped away to make better use of available resources.

Humility: celebrates the value of teamwork and communication, over heroic individuals and cautions against arrogance.

Dignity: while Anderson’s conception of dignity may seem dated to modern readers due to its reliance on stereotypical explanations of self-worth derived through collectivism in the east and individualism in the west, the overarching concept of dignity as a sense of deserved pride, self-respect, or a judgement of social worth, honor, and respect remains instructive as a value archetype.

“Value[s] are subjective interpretation[s]” that attempt to operationalize ethical constants into a framework for decision-making and resolving ethical dilemmas (Anderson, p. 27). Translating principles into value-statements forces leaders to “define the area of freedom for managerial action” (Anderson, p. 27) by identifying management priorities and setting the bounds of what leaders find desirable and acceptable within their span of control.

Everyone has a leadership philosophy, whether consciously examined and developed or not. If values define the area of freedom for leadership, leadership philosophy is the process used to take its measure and translate values to action. It is the world view or paradigm that leaders use to evaluate conflicts, tradeoffs, and resolve dilemmas. While everyone’s perspective is unique, Anderson posits five basic philosophical positions that combine in distinct ways to color the philosophical lens through which values are evaluated, prioritized, and put into action:

The invisible hand: posits that solutions should prioritize and be grounded in market forces that harness and coordinate profit seeking of individuals to maximize collective good.

A powerful driver for value creation, it has no inherent moral or ethical framework and can easily lead to sub-optimal outcomes at the system level when competitors saturate a market in pursuit of individual profits.

Stakeholder Analysis: posits that every stakeholder has a valid claim to the collective good, happiness, and fulfillment that comes out of decision making and should be considered based on their relative interest and power to influence outcomes.

While effective at maximizing benefits for those closest to decisions and outcomes, there is no guidance for how and when to prioritize when questions arise over whose happiness should be maximized when stakeholder interest conflicts.

The “Reasonable Man” conceit: holds that choices should be in line with those of an ideal, well informed, rational, or virtuous person.

The desire to embrace balance and compromise among competing stakeholders is laudable. But the “reasonable ideal” is a cultural archetype informed by social mores that can shift and prove unreliable over time.

Shaping Competitor Behavior: assumes that market-based tactics can be used to incentivize the competition to pursue cooperative system-level outcomes over individual gains by punishing rivals who leave the cooperative position and rewarding competitors who return over the long term.

While potentially effective for stable markets with known, rational, competitors with similar business models, the logic breaks down in dynamic or innovative environments. A temporary price cut to match a competitor in the hopes of forcing them to raise their prices will not work if the rival firm has a lower cost of production and can profitably sustain reduced prices indefinitely.

Enlightened Self-Interest: describes a system of good faith actions motivated in part on the expectation that others will reciprocate in ways that maximize freedom to operate in the marketplace.

Requires serious examination of competing goals for their interactive effects on outcomes and exposes the firm to risk if the expected “pay-off” does not materialize in the form of reciprocal good faith actions from others.

A clear advocate for the virtues of enlightened self-interest, Anderson argued that one’s leadership philosophy is not fixed or universal. It is both a skill and perspective to be developed, refined, and explored. The deeper you grow your awareness of your values and leadership philosophy, he argues, and the better aligned it is with your principles, the better your leadership will be no matter what challenges come your way.

The Values-based leadership model offers a useful framework to examine your leadership, identify your universal non-negotiables, and operationalize them as values to ensure that your leadership is worth following. It won’t be easy but outside perspective and knowledgeable guidance can help.

Let’s get to work!