Coping with Change: Cents and Sensibility

Leadership is synonymous with change. In fact, the Harvard Business Review described the work of leadership itself as prompting and demanding change by asking “hard questions” that “knock people out of their comfort zones,” and then going on to “manage the resulting distress.” Salesforce, the largest Customer Relationship Software provider in the world, has an entire category of content on its 360 blog dedicated to leading through change. Change management and leadership literature is awash with models, tips, and techniques to help leaders initiate and guide change to improve organizations from within.

However, comparatively little has been written about ways to process and cope with changes forced on their organization from the outside. If nothing else, the Covid pandemic has provided a clear demonstration of just how disruptive external change can be. Additional attention is clearly needed on coping with change imposed by external forces.

Change in response to adversity is nothing new. The tale of the lone entrepreneur pivoting in the face of dire circumstances to create value has a long and storied history. Theorists have observed similar phenomena at the organizational level as well. Starting in the late 1980’s Baumgartner and Jones developed the theory of “Punctuated Equilibrium” from a series of observations about how political bodies change over time. The theory states that groups and organizations organically create and maintain a set of mutually reinforcing cultural and performance norms. Under normal circumstances, this results in an invisible drive to maintain that equilibrium, thereby limiting the pace and scope of change to favor mostly incremental results over time. However, when something with sufficient force or scope comes along, it upsets the old balance causing new states of equilibrium to rapidly emerge, resulting in revolutionary rather than incremental change for those that survive the transformation. Punctuated equilibrium theory has been applied to businesses and organizations of all sizes to explain their tendency to oscillate between internally driven incremental change and revolutionary or rapid change, often in response to external forces. But how do leaders actually cope with changes they may not want and certainly didn’t ask for?

One way is to prepare for it in advance. In July of 2020, a series of Harvard Business Review articles from 2018 and 2019 were highlighted on this blog. These articles synthesized the lessons learned and proactive steps that businesses took to inoculate themselves against damage from external forces prior to the Great Recession of 2008. They demonstrated that the firms which took steps to prepare themselves for external shocks not only survived the great economic downturn but put themselves in the enviable position of outperforming their competition by double digits coming out of it and adding an average of 6 percentage points to total shareholder returns over companies that did not. Click here to check out the article from July 1st, 2020 for a deep dive on how to prepare in advance and how to find the fuel your organization needs to thrive in the face of economic downturns.

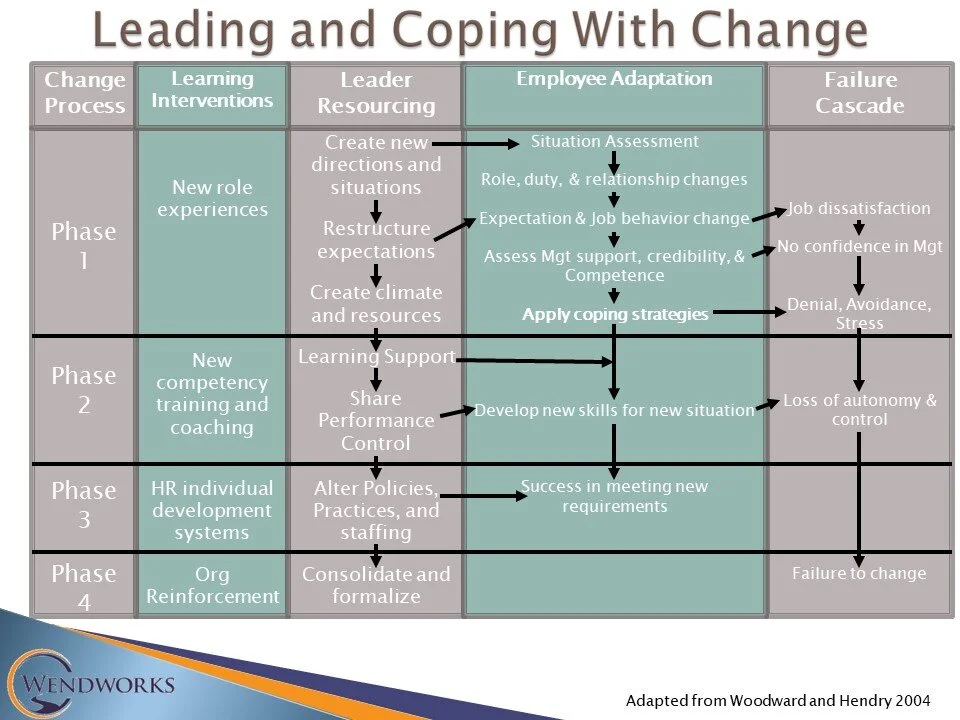

However, there is more to coping with change than preparation for economic downturns and surviving hard times. Woodward and Hendry point out in their article, Leading and Coping with Change, that there are always at least two perspectives to every change effort. For every change-agent leading the cause, there are those who will be impacted by it, whether or not they knew about it in advance or advocated for it in the first place. For every firm, there is a competitor ready to force their hand. For every leader there are people to whom they are accountable such as a supervisor, a board of directors, or shareholders who are in a position to impose or demand change. Often the question of whether one is leading or coping with change is a matter of perspective and where one fits within the power structure of the organization. Regardless of your position, no one is ever able to choose the change they want 100% of the time. However, we can control how we react individually and organizationally.

The uncertainty that accompanies adaptive situations will frequently render top-down, leader-driven, solutions impossible. This demands that organizations allow for change to come from the bottom up. When change is driven by shifting circumstances rather than organizational improvement efforts, the primary objective is typically to adapt and survive. Empowering those closest to the customer and the work being done to drive change, can be a critical strategy to help the organization change fast enough to keep pace with its environment in order to survive. In this situation, the work of the leader changes from that of change-agent to change manager and relationship maintainer. As Woodward and Hendry point out, coping with change ultimately has as much to do with the strength of interpersonal relationships, psychological capacity, and adaptability as it does with specific management techniques or leadership styles used within the firm.

“When change processes require fundamental shifts in the way organizational members think and act, the consequences of change can test… the organization’s capabilities and resources. Moreover, when people have been subject to substantial change already, or are operating in an uncertain environment that affects their future prospects, they may rapidly reach the limits of their capacity to absorb and respond to more change… What is needed, therefore, is a dynamic process model to show how change can successfully be absorbed.” (Woodward and Hendry, p. 156).

When faced with change that one did not choose, a different set of leadership skills are called for. “[In rapidly] changing situations, people need the help of others to construct their sense of self, create a sense of social order, and provide cues on how to act” (Woodward and Hendry, p. 166-167). Effective efforts are “intrinsically cognitive, involving sense making and translating understanding into action” in order to maintain coordination new interdependencies must be established (Woodward and Hendry, p. 167).

In other words, the when things really hit the fan or truly transformational change becomes necessary, the work of leaders must also change from a focus on execution and resource provisioning to the search for a viable replacement business model and organizational sense making.

Thurlow and Mills’ 2009 article in the Journal of Change Management provides an in-depth look at the critical role that sense-making plays in successful change efforts. Published in the wake of the great recession, they present a compelling and logical case for leaders to provide the vision and language for their teams. This vision and vocabulary are necessary, they argue, for organizational identities to be maintained, altered, or constrained in order to prevent organizational failure cascades like the one articulated by Woodward and Hendry five years earlier.

Frederic Nortier offered additional insight and a useful vocabulary in this area with his article on coping with change that offered a distinction between change and transition. Change, he argues, is an objective, time-bound, phenomena, focused on external measurable factors and designed to address the fundamental question of “what do we want?” In contrast, transition is the internal, psychological, and non-linear work necessary to process one’s feelings, emotions, answer the fundamental question “where am I” in this process and what does it mean?

So, how do leaders cope when change comes their way that they didn’t ask for and they may not want? Let’s review the checklist:

Prepare for negative change, including downturns, in advance. The better the gameplan going in, the better the odds of success coming out.

Put the change in context. Punctuated equilibrium theory provides a framework for what’s happening. In the same way that receiving a diagnosis often gives patients a sense of relief, having a name for what’s happening and a vocabulary to use with the team provides a sense of clarity and inspires confidence.

Err on the side of action. Focus on searching for the new business model, performance expectations, and cultural balance point. Communicate the revised vision as quickly and as often as possible throughout the organization rather than treading water or yearning for the old status quo to return.

Use the revised vision and a structured approach such as Woodward and Hendry’s Leading and Coping framework to communicate the leader’s job to be done, set employee expectations, clarify strategy, and insulate the team against a failure cascade. If managing up, use the framework to help your leaders do this for you and your peers.

Make time for sense-making. Change is hard and external or unwanted change is even harder. Don’t compound the team’s hardship by allowing them to feel like they are suffering for no reason. Focus on understanding the “why” behind what must change and help the rest of the organization to do the same.

Allow time for everyone, including yourself, to make the emotional transition as well as the immediate logistical modifications called for to survive the change and thrive as a team.

As the economy continues to recover from the coronavirus pandemic, organizations across the world will lead, cope, and struggle with change as we all assess the new reality of the business landscape. Objective changes will assert themselves first and organizations will once again figure out what’s working and what’s not. Firms will adjust their business model and get back to the business of executing plans and creating ever greater value for their customers. We will make the psychological and emotional transition too. The “new normal” will eventually be just normal. It will take a lot of work and it won’t be a straight line or an easy ride from here to there. I look forward to the journey and comparing notes along the way.

Let’s get to work!

References:

Grundy (2006). Rethinking and reinventing Michael Porter’s five forces model. Strategic Change

Heifetz and Laurie (2001). The Work of Leadership. Harvard Business Review

Macauley (2020). Retain employees to thrive in the new economy. Wendworks company blog

Macauley (2020). Necessity is a Mother… Wendworks company blog

Macauley (2020). The Shape of Power: Organizational Structure and Authority. Wendworks company blog

Thurlow and Mills (2009). Change, talk and sensemaking. Journal of Organizational Change Management

Woodward and Hendry (2004). Leading and coping with change. Journal of Change Management